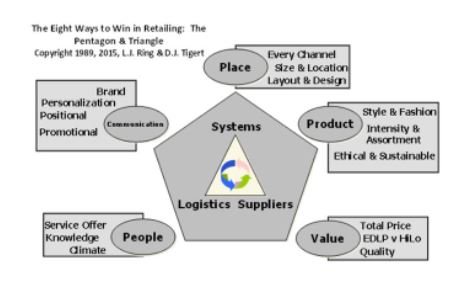

Gaining Competitive Advantage in Retailing?

The Pentagon represents the five major customer-facing activities through which retailers can visually differentiate themselves in the marketplace: place, product, value, communication and people. And the triangle supports the pentagon in the retailer’s goal to achieve operational effectiveness through superior systems, logistics, and supply relationships.

There are several ways to build competitive advantage in the retailing arena. At a generic level, students of strategy have identified three major strategic thrusts: cost leadership, differentiation, and focusing on a niche. A niche strategy is certainly a viable strategy when playing in the corners, or in limited segments of the market. However, as niche players grow more successful, niches inevitably become larger and less defensible. As a result, retailers are often faced with a choice between the market strategies of cost leadership and differentiation. We refer to differentiation activities as working on the pentagon, and cost-leadership activities as working on the triangle. Michael Porter has written that strategy is about being different, and that it is not operational effectiveness. It is the pentagon on which retailers register their differences in the minds of customers, but it is the triangle on which retailers achieve operational effectiveness, and while operational effectiveness is not strategy, if a retailer is not operationally effective, then that is goal number one.

All retailers have a position in the marketplace on all five corners of the pentagon. The pentagon represents what the customer can see when walking into the store, visiting the website, or looking at advertising and promotion—in other words, customer-facing activities. There are five major ways in which retailers can visually differentiate themselves from other retailers in the marketplace. All five corners of the pentagon also have important subcategories.

Most retailers do have a paradigm about how they are running the business. However, the greatest single weakness of most retailers is that they don’t often go back and re-examine that paradigm—re-examine whether what they are doing in all the subcategories of the five corners of the pentagon is still the best way to run the business—in light of a changing economic environment, a changing consumer environment, including consumer buying behavior patterns, a changing technology environment, and a changing competitive environment.

The stronger a retailer is on the pentagon, the more customers it can draw to shop in its stores or on its website. The ability to draw customers from great distances powers higher sales productivity in bricks-and-mortar stores. Likewise, an appealing and easily navigated website also can be attractive in drawing customers to a retailer online. Winning on the pentagon means driving the top line.

The Place Variables

Every Channel

With the advent of online shopping, retailers need to be where their customers expect to find them, whether that is in bricks-and-mortar stores, in mail-order catalogs, or online. The idea of omnichannel retailing is to be able to deliver a seamless, integrated experience for the customer across all channels.

Store Size

One of the issues related to the bricks-and-mortar place is store size. The way to think about store size is for the retailer to take each department it wishes to be in and ask how much space it takes to win in that particular department in the store. This question is particularly important if the retailer decides it needs a dominant assortment in that particular department. Then, add up the required square footage in all the departments that you wish to be in and that determines your store size.

Of course, size is not an issue on the internet. Theoretically, a retailer can have an endless aisle on its website, provided it has the capacity and technology to deliver an infinite assortment.

Location

A second subcategory related to place is location. There are several issues related to location. One issue retailers don’t ask themselves very often is what the optimal distance is between stores. This issue is especially appropriate for the large and/or growing chain. One thing seems clear: If a retailer has stores that are two miles apart, the farthest each store can draw is one mile, which is half the distance to the next store. Even if that store down the road two miles is a competitor, but is a very similar store, the answer will still be the same. The farthest a retailer can draw a customer is half the distance to the next similar kind of store. Most traditional department stores suffer from this problem. As most local and regional department store chains grew during the last 40 years, they became the anchors of every suburban shopping center in the region. Now, the farthest those stores can draw is half the distance to the next mall.

If you limited your sales-per-square-foot opportunity by locating your stores relatively close together, there is only one way to still ensure good operating profits per square foot and that is by having very low operating expenses per square foot. There are several retailers that understand that paradigm and have learned to make a lot of profit per square foot on relatively low sales per square foot by deciding to become cost leaders, and to become leaders in productivity.

Another location concern has to do with not just how far away my next store is, but the quality of the location itself. Many chains have built location models to help project sales per square foot for new and existing locations. Wal-Mart has a 1,000-variable traiting model that it uses to predict what its volume will be at a particular location. In addition, that model also is used to divide all the Wal-Mart stores into groups that have different merchandise mixes that are then fine-tuned to a particular kind of population, in a particular climatic zone, with a particular buying behavior pattern expressed by consumers in those markets.

Layout and Design

Another subcategory related to place is layout and design. The retailer that views layout and design as an expense rather than an investment in competitive advantage doesn’t understand how people shop stores, and doesn’t understand the role of store environment as a critical determinant of store choice.

Some retailers spend a lot of money per square foot for design and construction and others spend very little. This decision depends upon which business a retailer is trying to be in and whether the strategy is to be a low-cost player or whether the strategy is one of high service/high margin. But, layout and design is just as important as any other element of place or any other element in the overall marketing strategy.

It also is important to look beyond what is spent to build and open the store. The more successful the store, the more traffic it attracts and the faster it becomes tired. Chains also need to spend money regularly to renovate and refresh their existing stores. For example, Zara and H&M refresh their stores every two years.

Online Offer

The online place, the website, is not so much a question of size and location, but more a question of online offer. For example, an office supplies retailer might have a website that can serve three segments of the market, end consumers, small businesses, and corporate customers. The website might be adapted for both mobile and tablet access. The offer also could include useful apps, blogs, and social media access such as Facebook, Twitter, and Pinterest. Another important issue for the online offer is what security features are available.

System Usability and Navigation

Just as store layout and design are important to bricks-and-mortar stores, so, too, is system usability and navigability to the website. Ease of use is very important here, beginning with the ease of a login. Then, other important features include the ease and completeness of product search results, stock availability messaging, and product details. Customers appreciate product recommendations, personalized content, and help centers and the availability of live chat. Finally, an easy checkout experience also is critical.

The Product Variables

Merchandise Intensity

Merchandise intensity in the bricks-and-mortar store is measured by how many dollars the retailer has invested per square foot at cost in inventory. In general, it has been shown to be more or less true and consistent across retail sectors that higher merchandise intensity leads to higher sales per square foot (up to a point, after which additional inventory becomes counterproductive as the store becomes hard to shop). In the year before Macy’s went into Chapter 11 bankruptcy (1992), the company reduced their inventory 18 percent, most likely in an effort to produce desperately needed cash flow. Not too surprisingly, Macy’s sales fell 18 percent in that same year.

There is a relationship between stock intensity and sales density. There is another problem, of course, because the retailer that chooses to stock high and deep still has to figure out a way to get it out of the store. And, there are only two ways to get a lot of merchandise out the door. One way is to price it hard—which means being the cost/price leader. The other way is to sell it hard—which means being the service leader.

The concept of merchandise intensity has little meaning for the retailer’s website because there really isn’t anything like inventory per square foot in the online world.

Merchandise Assortment

The second major subcategory related to the product corner of the pentagon is merchandise assortment. A key question here has to do with how a retailer gets the right assortment. Does the retailer, for example, depend upon a set of buyers who by some well-calibrated instincts are very good at going out there and always buying the right merchandise at the right time? If you are in the fashion business, that approach takes a lot of faith in the buyers being able to consistently, time and again, go out and find the right merchandise for their customers.

Alternatively, some believe the right merchandise in the store can be consistently generated only by being market driven. Being market driven means that the retailer must find a way to let his or her customers tell the retailer what they want.

By using the right measurements, a retailer can soon discover whether an item is a winner or a loser. What isn’t known, however, is all the items not yet tested. Or, is more testing needed—how much, and how often—with bellwether stores or photos, or whatever? How many items should be tested, for how long, to determine their potential? The concept is the same for both food and apparel, but it’s a lot easier for a food retailer to do that on a systematic and continuous basis.

Another aspect of the merchandise assortment subcategory has to do with assortment strategy. The key here is what the retailer is trying to offer the consumer and what role assortment plays in that offering. For example, a convenience assortment means we are in the business of saving people time rather than money, and we are not offering a wide choice. On the other hand, a power or dominant assortment means “I’m committed to offering the largest assortment in the marketplace.” Category killers such as Toys “R” Us in toys and games, Home Depot in hardware/home improvement, and Best Buy in consumer electronics come to mind.

A competitive assortment is one pretty much the same as that offered by most others in the marketplace. A differentiated or focused assortment means a unique assortment that can’t be found elsewhere. It means you are the only place where the customer can find this assortment in the area. Examples include the Body Shop, Papyrus, and Anthropologie. Private-label brands also can provide differentiation. For example, you can buy Gap jeans only at the Gap, and you can get Craftsman tools only at Sears.

The warehouse clubs such as Costco and Sam’s Club offer velocity assortments. This strategy means that the store carries only one SKU per product class. They ask the customer to give up choice in order to get a very low price. Another price-focused assortment strategy is opportunistic assortment. In this strategy, everything in the store is bought on deal—something less than the full cost of goods sold price to suppliers. Dollar General follows this strategy, as do T.J. Maxx, Marshall’s, and Ross Stores.

Within assortment strategies, retailers also define categories in terms of width and role with descriptors such as leadership, authority, complimentary, traffic builder, assortment enhancer, and impulse. Depth of assortment refers to the proportion of the category devoted to entry, good, better, and best lines.

These assortment strategies apply to both bricks-and-mortar and online stores. However, a key question retailers must ask is whether the online assortment should be the same as the in-store assortment, or smaller or larger, and what the implications are to customers of a decision to be smaller or larger online.

Style and Fashion

We generally think of apparel when we think of style and fashion. However, there also is style and fashion in furniture and home furnishings, consumer electronics, and even in food—just check out a Whole Foods Market or a Wegman’s grocery store.

In apparel, consumers have a vocabulary they use to describe fashion items they purchase. They use the words “very latest, most fashionable,” “current, up-to-date,” “everyday, basic conservative,” “contemporary,” and “classic.” One way to visualize a fashion market is to build a perceptual map of, for example, fashion (on a continuum from high to low) versus value for the money (on a continuum from best to worst). The resulting map would show four quadrants, with one being high fashion/worst value, such as Neiman Marcus (frequently referred to as Needless Markup). A second quadrant might be low fashion/worst value, where Kmart might come to mind. A third quadrant would be high fashion/best value, which is where the fast fashion players such as Zara and H&M reside. The fourth quadrant would be low fashion/best value and might include off pricers such as T.J. Maxx.

Similar thinking could be applied to other categories, such as consumer electronics or furniture, where, once again, retailers must consider the perceived uniqueness of their offerings along with prevailing trends.

Ethical and Sustainable

In recent years, ethical sourcing and sustainability have become significant issues for retailers. These terms imply that the products a retailer sells are certified or accredited as being manufactured and sourced ethically and/or sustainably in a way that minimizes harm to the environment and complies with the retailer’s philosophies.

Value

Value is what you pay for what you get. It’s a combination of the price and quality variables, although it appears more and more driven by price. In most retail sectors, price is 50 to 60 or more percent of the total value equation in the mind of the customer. In food, price is 90 percent of the value equation, while in fashion the price/quality relationship is more like 50/50. And, in some categories like fashion, there is more than one value position. For example, a retailer can be low price/low quality such as Wal-Mart and be high value to a particular market segment. Or, a retailer can position itself a little further upscale, as has Kohl’s, with modest quality/modest prices, and be high value to another market segment. And, so on—until we find a chain such as Neiman Marcus operating with among the highest prices and the highest quality and perceived as good value by a relatively small, very upscale segment of the market.

As we consider online retailing, we need to think in terms of total price, including any delivery charge that may apply.

Another consideration is how the retailer will set prices. Two often-used strategies are everyday low(est) prices (EDLP) and hi-low pricing. EDLP is just what it sounds like, while hi-low means the retailer has a small percentage of its items on sale each week, with the rest of the items at full price. Wal-Mart is probably the most well-known proponent of EDLP, while Target and Kmart are hi-low pricers.

The People Variables

The people corner of the pentagon also has three subcategories: service, knowledge, and climate.

Service Offer

The service subcategory has to do with the service levels the retailer wishes to execute. There is a continuum of customer experience retailers might offer from self-service to high-level retail employee service. The service level a retailer needs to execute depends upon the type of retailer it wishes to be and how it wishes to be positioned in the consumer’s mind. For example, executives in a department store chain might ask what the longest period of time is that can pass when a customer enters a department before being acknowledged by a sales associate. Or, a more self-service organization might set a service standard in terms of how long it takes a customer to actually make a purchase and leave the store. For example, Wal-Mart’s standard is three’s a crowd. Three’s a crowd means that once each checkout station in a Wal-Mart store has two people standing in line, the store manager must open another checkout station. This standard says something about the number of checkout stations a particular store needs and about labor scheduling and employee training.

Another way to think about service is to measure service intensity. Service intensity is defined as the number of square feet being managed by each full-time equivalent employee. A high number here indicates relatively low service and coverage, while a low number means high service and coverage.

Online, people also offer service. For example, the retailer might provide a call center or offer live chat.

Knowledge

The second issue on the people corner of the pentagon has to do with the knowledge levels a particular retailer wishes its employees to possess. There are only two ways for an employee to obtain a certain knowledge level. One way is for the retailer or supplier to train the employee. The other way, of course, is to hire employees, sales associates for example, who already have that knowledge.

Online knowledge might be provided by on-site reviews and by product comparisons.

Climate

The third issue related to people is the concept of climate. There are two dimensions to climate. The first dimension has to do with what customers think about what it is like to shop at a particular store. The second dimension has to do with what employees of a particular store think about what it is like to work there. A third question has to do with consistency—do the climate the customers experience and the climate the employees work in need to be the same? A major challenge for retailers is to ensure consistency of climate and experience for customers from website to store and vice versa.

Communication

The last corner of the pentagon is communication. For many retailers, communication is a tough problem. It is tough because if a store or chain doesn’t win on place, with a better or bigger or better designed location or website; doesn’t win on product, more intensity or better assortment or the right fashion position; and doesn’t win on value or service, what can it say about itself? If the chain isn’t a winner on one or more of the five corners of the pentagon, about all that’s left to do is run a sale—in other words, do promotional advertising to generate immediate response.

Positioning advertising is communication that tells the customer a retailer wins on one or more corners of the pentagon. Positioning advertising is Nordstrom talking about having its massive assortment of men’s suits or its thousands of pairs of shoes. Similarly, Wal-Mart or Food Lion advertising everyday low prices (EDLP) also is positioning—positioning themselves as the low-price leaders in their markets. Bunnings, the Australian home-improvement retailer, boasts of lowest prices, widest range, and best service.

Another important aspect is the role of the brand in positioning and communication. This includes not only the store brand, but also the various product and service brands carried within.

Online retailing offers additional opportunities to personalize communications from retailers to customers, allowing information, offers, and recommendations provided to customers to be tailored specifically to them.

Changing the Pentagon

The pentagon is the retailer’s face to the public and to its customers. The corners of the pentagon hold few secrets from competitors, because they are all very visible. Why do some firms fail to re-evaluate their position on the corners of the pentagon? The most obvious answer is that many retailers are not systematically tracking the changing consumer, economic, and competitive environment, and, as a result, they are not really aware of what is happening out there. Frequently, the environment is changing faster than the retailers.

Another explanation is that companies sometimes get old and tired and fail to rejuvenate their management. They end up suffering from what has been referred to as paradigm paralysis. Or, some companies are unable to change on the corners of the pentagon because they don’t have the financial resources. Frequently, this problem surfaces after a private-equity buyout. After a buyout, of course, the first call on the retailer’s cash flow is the interest on the debt—not fixing the place, website, product, service, or advertising, and so on.

The pentagon’s corners are easy to see and understand. But, for most retailers, it is difficult to execute on those corners in such a way as to build a really sustainable competitive advantage. And, once set on a particular corner of the pentagon, the bottom-line focus most retailers have on ROI tends to insure inertia.

Often, it is new players who invent or develop new sources of competitive advantage in retailing. Frequently, the incumbents are reluctant to change because they have made an investment in the present. The new players may come from many backgrounds. Sometimes they are former losers who have learned something—Sol Price at FedMart and then Price Company comes to mind. Or, maybe they left a winner, such as the founders of Costco, former senior managers at Price Company. Sometimes, they are brand new entrepreneurs, such as Build-a-Bear. Sam Walton was a successful Ben Franklin franchisee who tried for years to get Ben Franklin to commit to discounting in small towns. Finally, when Franklin would not support the concept, Walton did it himself. Bernie Marcus and Arthur Blank were fired from Handy Dan Home Improvement Centers and went on to found The Home Depot. TJX grew out of Zayre, and so forth. Amazon.com has transformed the industry, starting with books, and then moving on to other categories, by bringing retailing to the internet.

The Triangle

The pentagon has to do with all of those things a retailer does that the customer can see—the customer-facing activities. Behind the scenes, however, often not seen at all by the customer, are the elements of the triangle. These elements support the pentagon and, for the most part, working hard on each of them is the way retailers reduce their costs. They reduce costs through better programmed systems, logistics, and supply relationships.

It is the pentagon that drives the top line (high sales per square foot), but it is the triangle that drives the bottom line (high profit per square foot).

Systems

Systems provide the mechanisms for controlling flows and operations. They are carriers for operational decisions and business processes. The information systems supply can provide a competitive advantage if timely action can be taken. Increasingly, retailers need systems that allow them to manage item by item, store by store, and online.

Logistics

This corner of the triangle concerns the movement of goods from suppliers to stores and encompasses distribution centers, online warehouses, and transportation. It is a major factor in operations and financial performance that relates to time and inventory (turns). In many retail supply chains, there exist significant opportunities to reduce loss from theft, breakage, spoilage, intentional fraud, and unintentional inaccuracies.

Suppliers

Supply relationships determine deals, terms, delivery quantities, dates, and so on. Relationships range from adversarial to cooperative.

Triangle Activities

The many triangle activities also can be categorized as quick response, replacement of labor by technology, merchandising and space management, and supply chain and logistics.

Quick response (including automatic replenishment) includes an alphabet soup of activities such as EDI, UPC/barcode, POS, CL, PSS, VMI, perpetual inventory, programmed supply relationships, and information sharing.

Replacement of labor by technology includes front-end scanning, labor scheduling systems, electronic shelf stickers, fully automated warehouse/distribution centers, check robots, automated picking lines, store security systems, and environmental controls.

Merchandising and space management includes SKU data capture, direct product profitability, rapid intensification and delisting, and modularization in store design.

Supply chain and logistics includes the greening of the chain, more global activity, RFID growth, focus on risk management, supply chain vendor consolidation, and voice technology.

In general, the idea is to build a productivity loop—to make an investment in lowering costs by having better logistics, or better supplier relationships, or just-in-time delivery, or systems for better inventory control or better labor scheduling, or whatever. Once costs have been lowered, the company can then reduce its margins. Lower margins mean lower prices, and lower prices mean the company’s value equation improves. An improved value position results in higher sales per square foot. Higher sales per square foot mean lower costs—as a percent of sales. And, lower costs mean that the retailer can reduce gross margins, and thereby prices, again.

The ultimate objective of working the triangle is to support the pentagon and develop sustainable price leadership. Companies that are most successful at this typically are or move toward consistent or everyday low prices, rather than hi-low promotional pricing.